UCL Inaugural Lecture - Drum machines, driverless cars and the politics of artificial intelligence

This is the text and some of the slides from my inaugural professorial lecture at UCL, which took place on 4th October 2023

Tradition dictates that an inaugural lecture should be a little bit autobiographical and a little big pedagogical. Some of you will know that I come from a family who trade in showbusiness. This is probably as close as I get to showbiz, so I am going to try to mitigate my family’s disappointment by dropping occasional references to the performing arts among my citations.

I have, like everyone else, everywhere, spent the last year worrying about artificial intelligence. I am part of a team working on a research program called Responsible AI. Earlier this year we were given funding for five years, but in the same week that we launched, we were told that AI was going to end the world before we were even halfway.

The AI scare stories like this were driven by hype about a chatbot. ChatGPT, launched in November last year, is a generative AI system that uses a large language model to do something that on the face of it is quite simple: predict the next word in a sentence.

The latest version of this model is built by feeding it most of the text available on the Internet, using massive amounts of computer power and some clever algorithms to model language so that it is able to spit out something that looks like more of the same.

It can do you plausible pastiches of text in different genres, which has caused panic among those of us whose job involves churning out plausible-seeming text or asking our students to do the same.

Since this thing went public - and there was a lot of fanfare about it being the fastest growing app in history - people have been scrambling to work out what it means for society.

A lot of the excitement has been about how this is not just an AI that can do one thing really well, but that it might be a step towards an artificial general intelligence. Not just being really good at chess, or recommending Netflix programmes, or translating text, but being able to generalise.

There’s a grand tradition of this sort of hype in artificial intelligence.

With the understanding that there really is no business like showbusiness, we might call it the “Annie get your Gun'' fallacy - Anything you can do AI can do better - whether it’s Chess or Driving or Paralegalling or Radiology or Music or Psychotherapy.

AI optimists have suggested that artificial general intelligence is just around the corner. And it seems that the more excitement there is about the technology, the more misanthropic the statements about humans become.

Many people’s response has been solipsistic. We seem happy to swallow the hype and believe that AI is indeed an assault on what it means to be human. We worry about AI taking over our jobs, and these worries are supported by studies that tell us how quickly we will be made redundant.

And the people currently in control of the technology also tell us that we should worry about the risks of what some of them actually call “God-like AI”.

This is Sam Altman, visiting UCL back in May, talking to Azeem Azhar. Sam Altman is the head of Open AI, the company that makes ChatGPT. He began his company as a not-for-profit and then made it pro-profit once it became clear that there could be lots of it. He came to UCL as part of a global tour, which helped establish him as the current face of AI.

Outside the Sam Altman event there was a small protest. Some students were warning that the dangers of AI were existential. The strange thing is that Sam Altman also subscribes to the view that AI presents an existential risk. He worries that it could be, as he puts it, “lights out for all of us.”

He was one of the signatories of an admirably brief, one-sentence open letter, that claimed ‘Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war’.

It seems odd to extrapolate from a pastiche machine to the end of the world as we know it. But the imagined apocalypse is part of the hype surrounding the imaginary capabilities of artificial general intelligence. It’s being used to create a sense of urgency, trying to bump society into accepting the inevitable logic of AI.

And it’s an argument that has been astonishingly influential. Journalists love it, and it seems that governments do too.

In a month’s time, Rishi Sunak will be hosting a Summit on AI Safety at Bletchley Park - former home of Alan Turing and his fellow World War Two boffins.

The government say they are worried about two things. First, the misuse of AI by what they refer to as “bad actors”, and second, they’re worried about the technology running out of control if it is not “aligned with our values and intentions”. They mean “our” as in the human race, not as in Britain or the current government.

The way they talk about the technology, it’s as though it’s an external, magical force, not a thing made by people who have particular ends in mind.

So I think we need to put people back in. We need to think about AI differently.

I’m interested in the politics of AI. At its simplest, politics is about who gets what and how. It’s about who wins and loses and the processes for making decisions about such things: processes that include some and exclude others.

Which means we shouldn’t see this as a power struggle between humans and robots. That way of looking at it benefits the people trying to sell stuff. They would like us to believe that the future they want is merely the next stage in society’s inevitable progress.

AI will, like all technologies, empower some people and disempower others. So we should be asking how it can buck the trend of past technologies, which have tended to benefit people who are already privileged.

This view of AI changes how we think about the opportunities and risks of new technologies, and it changes how we should view the responsibilities of companies like OpenAI and the policymakers who are currently backing them.

In a bit, I’ll be talking about music, automation and drum machines - where some of the solipsistic fears raise their heads. But first, let’s do self-driving cars.

Self-driving cars

I first got interested in self-driving cars in 2016. There were some high-profile crashes, in which people had been killed in prototype vehicles. Then in 2018, in Phoenix Arizona, Elaine Herzberg had the misfortune of becoming the first bystander to be killed by a self-driving car.

Herzberg was a homeless woman, walking her bike across a four-lane road at night. She was hit and killed by a self-driving Volvo that was operated by Uber. The car was travelling at 38 miles an hour and it didn’t slow down. This is an informal memorial to her.

The reason to look at this sort of thing is not a morbid one. It’s that, when technologies go wrong, we can learn things about the assumptions that shape them, assumptions that are hidden when things are going well.

The story of the self-driving vehicle that their developers like to tell is one of autonomy. They talk about autonomous vehicles, where you take a normal car, pluck out the human and replace it with the sensors, computing power and data that it needs to see the world, identify other objects, predict what they are going to do next and plan a safe route through them.

By plugging in an omniscient computer, the hope is that the technology will eliminate the risks that come with fallible human drivers. The idea is that a powerful enough AI can be fed enough data to learn everything it needs to adapt to the world as it finds it.

The death of Elaine Herzberg and the investigation that followed revealed the lie of autonomy. The Uber autonomous vehicle was not as autodidactic or as independent as Uber wanted us to believe. The technology didn’t work, but the company blamed the crash on the safety driver, who was supposed to be in charge of the vehicle.

This pattern of blaming the human is fairly typical - Madeleine Elish has called the human in the loop the “moral crumple zone”. And I should actually say that the first person that got blamed was Elaine Herzberg herself for being in the wrong place.

Now, all crashes have multiple causes. The crash investigation revealed how dependent the car was not just on its sensors and its AI - and the engineers knew at the time of the crash that the AI wasn’t up to the job - but also a supportive infrastructure, predictable, well-behaved road users, a safety driver who in this case had been given very little training and a benign policy environment. The governor of Arizona asked almost nothing of Uber in exchange for giving its roads over as a laboratory.

This crash ended Uber’s hopes of winning the imagined race, but didn’t dampen the enthusiasm of others. Elon Musk has continued to assert the inevitability of the autonomous vehicle. Musk and Tesla have doubled down on an approach that says they don’t need fancy sensors or special roads. It’s just about more and more AI.

If you look at the deadlines he’s set himself, it doesn’t seem to be working. But that hasn’t stopped Tesla from charging its customers thousands of dollars for something they call “Full Self-Driving”, which is sold as being just around the corner.

Musk’s story is not just about robotic autonomy. It’s also about human autonomy - Your freedom to go by car wherever you like and your freedom from regulators who might want to stop you.

It’s part of a longer story about emancipatory technologies, which promise to free humanity from various burdens

The anthropologist of science Bruno Latour, who died almost a year ago, said that the development of technologies involved a realisation not of freedom but of what he called “attachments of things and people at an ever expanding scale and at an ever increasing degree of intimacy.”

If you live in Phoenix, San Francisco or a couple of other places, self-driving cars have now become a common sight. You can now see and use self-driving vehicles and in many cases there is no-one in the driving seat. They are mostly safe. But they are imposing themselves on these cities in other ways. Rather than moving fast and breaking things, the technology has a tendency to move slowly and clog things up. Society is being forced to come to terms with the attachments of self-driving cars.

The companies involved are very secretive, even if the experiment looks like a public one. So a lot of the data collection is happening on social media. There have been reports of robot cars blocking roads, failing to detect construction sites, nudging into buses and getting in the way of emergency services.

The PR response of one company, Cruise was, like an abusive partner, to try to make us feel even worse about ourselves. This was a full page ad in the New York Times in July.

Some residents are not happy…

As with most AI, the promise is a technology that will solve our problems by learning and adapting, and that the rest of the world does not need to change. The reality is that the world does have to adapt.

If you’re an engineer, the challenge of getting a computer to drive like a person is really compelling, but it’s an odd approach. It’s odd to get a camera to look at a traffic light and detect its colour when the traffic light could just communicate its status directly to a connected car? Then again,it seems odd to have little, soft, fleshy pedestrians sharing the road with big lumps of steel. The challenges of this open, interactive system are vast. In engineering terms, it would be far easier to find ways to close the system, to reduce uncertainty and contingency.

A couple of years ago, I did a set of interviews with self-driving car developers, and most of them admit in private the ways that they are trying to make the problem easier. Most companies are using lidar-based 3D maps so that cars can know what to expect. And they stick to the roads that they’ve mapped, where they know they’re not going to see too much trouble.

Back in 1983, the UCL psychologist Lisanne Bainbridge wrote a brilliant paper on what she called the ironies of automation. One of these ironies was that automation doesn’t make the problems of human labour and human error disappear. And in many cases adds to the complications.

Since Bainbridge published this paper, there have been some lovely sociological studies of robot vacuum cleaners and supermarket self-checkouts that reveal the human effort required to compensate for the limits of technology.

Like the Wizard of Oz, self-driving car developers want us to pay no attention to the man behind the curtain.

Even if we can’t see anyone in the driving seat, there are plenty of people keeping the show on the road. There are remote controllers, mapmakers, data labellers, maintenance people, cleaners, software engineers and lobbyists and more.

The companies claim that these support staff, like the people doing content moderation to make ChatGPT less toxic, are temporary while the system learns its way to full autonomy. But if the technology succeeds, we will see a permanent reconfiguring of infrastructure and human labour.

If self-driving vehicle companies manage to persuade cities that they do more good than harm, we will see pressure to upgrade infrastructure to make our cities more machine-readable.

As Harro Van Lente has argued, technological promises can quickly become demands upon society. There will also be pressure on other road users. One technology developer that we interviewed said their job would be easier “if people could agree to cross at zebra crossings”.

On which point, I should mention that it later emerged that one of the reasons the self-driving Uber failed when it came to Elaine Herzberg is that the engineers had decided that objects in the road but not in pedestrian crossings couldn’t be pedestrians.

A century ago, particularly in the US but also here, there were changes to rules and social norms that favoured cars. And this has shaped how we get about, how we now live with risk and how places get built ever since.

As the historian Peter Norton has argued, before we rebuild our world around the next new way of getting about, we should think about who’s really going to benefit.

Drum machines

OK. Handbrake turn. Next case study.

I am an occasional mediocre drummer, so this one is personal.

Let’s start with a human. This is the drummer Clyde Stubblefield playing with James Brown in 1970.

The song is called Funky Drummer. Even if you don’t know it, I promise you’ve heard it before. It’s one of the most sampled drum breaks of all time. The phrase has been looped, often sped up, and used on more than 1,000 other tunes.

If we want to, we could automate this pretty easily. It is, at its simplest, a set of 16 semiquavers. Conveniently and coincidentally, this makes the maths rather easy for a computer. Each beat fits neatly into a grid, which makes it consistent, and once it’s in the machine, it won’t slow down or speed up.

That’s my version of the funky drummer. I think we can all agree that it’s missing something. Most of the time we don’t want all of our music to sound too much like a machine. There’s something ineffably human about the way that Stubblefield plays that makes his drum loop so popular, more popular than a mechanical one would have been.

That said, the history of drum machines suggests that there are plenty of people who think that both easy and desirable to automate drummers.

The history of the drum machine is very long.

In the brilliantly-titled Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, published in 1206, Ismail Al-Jazari describes a mechanical boat, powered by water. This would have been a toy to entertain royal guests. On the deck of the boat, is a model band, whose drummers play patterns set by adjustable pegs inside the boat’s guts.

The roboticist Noel Sharkey, who recreated this thing for a TV programme a few years ago, claims that this drum machine counts as one of the first programmable robots.

But to find a drum machine that truly threatens the livelihood of a practising drummer, we need to move fast forward to the 1950s.

This is a Wurlitzer Sideman, first sold in 1959. It works by rotating an arm across a circle of electrical contacts. There are 48 rows, which is neatly divisible into 4s and 3s so that it can do you a samba, a shuffle, a waltz, a tango or various other beats. To increase the tempo, you increase the speed of the spinning arm.

The advert is clear on its job-stealing ambitions - it promises “A full rhythm section at your side”. Despite how it sounds, this thing spooked the UK Musicians Union, who dismissed it as a ‘stilted and unimaginative performer’.

The Union’s reaction to the Sideman follows in a long line of musicians’ concerns about musical innovation. Over the last 300 years, musicians have complained loudly about the piano, the mechanical flute, the metronome, the player piano and most recently, auto-tune.

John Philip Sousa, who was the most popular musician of his day, wrote an essay in 1906 on what he rather brilliantly called “the menace of mechanical music”. He was referring to the mediation of the relationship between performer and audience with the arrival of the phonograph, which he called a “substitute for human skill, intelligence and soul.”.

He admitted that his interests were economic ones. He was making huge amounts of money from touring his band and selling sheet music. But he also claimed that innovation was tearing the soul out of what he considered real music.

And he had a point - technologies don’t just solve problems, they change our expectations, and they change our sense of what’s normal. Auto-tune corrects a singer’s pitch but it also changes how we expect music to sound.

Back to the drum machine. This is Roger Linn - drum machine pioneer. From the 80s onwards, his drum machines gave musicians for the first time sounds that sounded like real drums, sampled from real drums. When Linn was creating his first drum machines, computer memory was expensive. So when clumsy humans would finger-drum their beats into the machines, the machines would round each beat up or down to the nearest one. On this drum machine, it’s called “error correction”. It would later be called quantising. This was sold as a solution to imperfect human timekeeping.

But with more memory, Linn realised that he could give programmers more control, not just by allowing for more precise error correction, but by shifting beats in ways that, Linn thought, would feel more human. This was sometimes called swing - on this drum machine, you can move in increments between straight and shuffle, but it’s the same thing.

Let me demonstrate swing with my little drum machine. There are still 16 notes, but alternate notes are made slightly later. On my little drum machine, I’ve swung the funky drummer, first a lot, so it sounds a bit New Jack Swing, before dialling it back so that it’s swung just fractionally.

Stubblefield’s playing has a swing to it that comes from his accumulated expertise. A big part of a drummer’s knowledge is tacit - impossible to put in words - and it is also embodied. Stubblefield’s notes come from the dance of his limbs.

Musicologists have studied the Funky Drummer break and found that his semiquavers have a swing ratio of 1.1 to 1, where 1 to 1 is perfectly straight and 2 to 1 would be a shuffle. (They also found that the backbeats on two and four are slightly later than they should be).

Talking about swing in this way is heretical to jazz musicians. Fats Waller was once asked to define swing and replied ‘If you gotta ask, you ain’t got it’. In jazz, swing comes from experience, wisdom, the body and also from interaction with others in the moment. It might be possible to replicate the sound, but there will still be something ineffable about it.

The technophile view is that these technologies don’t substitute for humans, but they allow musicians to understand new things about music and go to new places. Drum machines and other electronic instruments were used in ways far outside their designers’ intentions. Asking what is better - a drum machine or a drummer - is to miss the point. They are different. The most innovative musicians, from Stravinsky to Stevie Wonder, saw music technologies not as a solution to a problem, but as a new set of possibilities. And this innovation changes our sense of what a drummer is and what drums can be.

According to a recent book by Dan Charnas, the 21st century’s most important drummer was not a drummer at all, but a producer.

J Dilla’s instrument was an MPC sampler, also invented by Roger Linn. This could grab bits of sound, chop them up, bend them and assemble them in new ways. The sampler allowed its programmers to fit into a grid, to go off-grid, or to add different amounts of swing to different sounds. According to Charnas, Dilla’s disorientating experiments with swing, which are exceptionally hard to replicate on a drum kit, have not just created a new musical aesthetic, but also changed our collective sense of rhythm.

Now the obvious, and mean, response to all of this, is that drumming doesn’t require intelligence - human or otherwise. (We could actually say that driving doesn’t require much intelligence either). But when we see something being automated, it prompts the question of what is special about that thing and what might be lost as new technologies give us new capabilities.

Musicians, despite their hard-won skills, can’t be complacent. If you’re a drummer, maybe the algorithm is indeed going to get you.

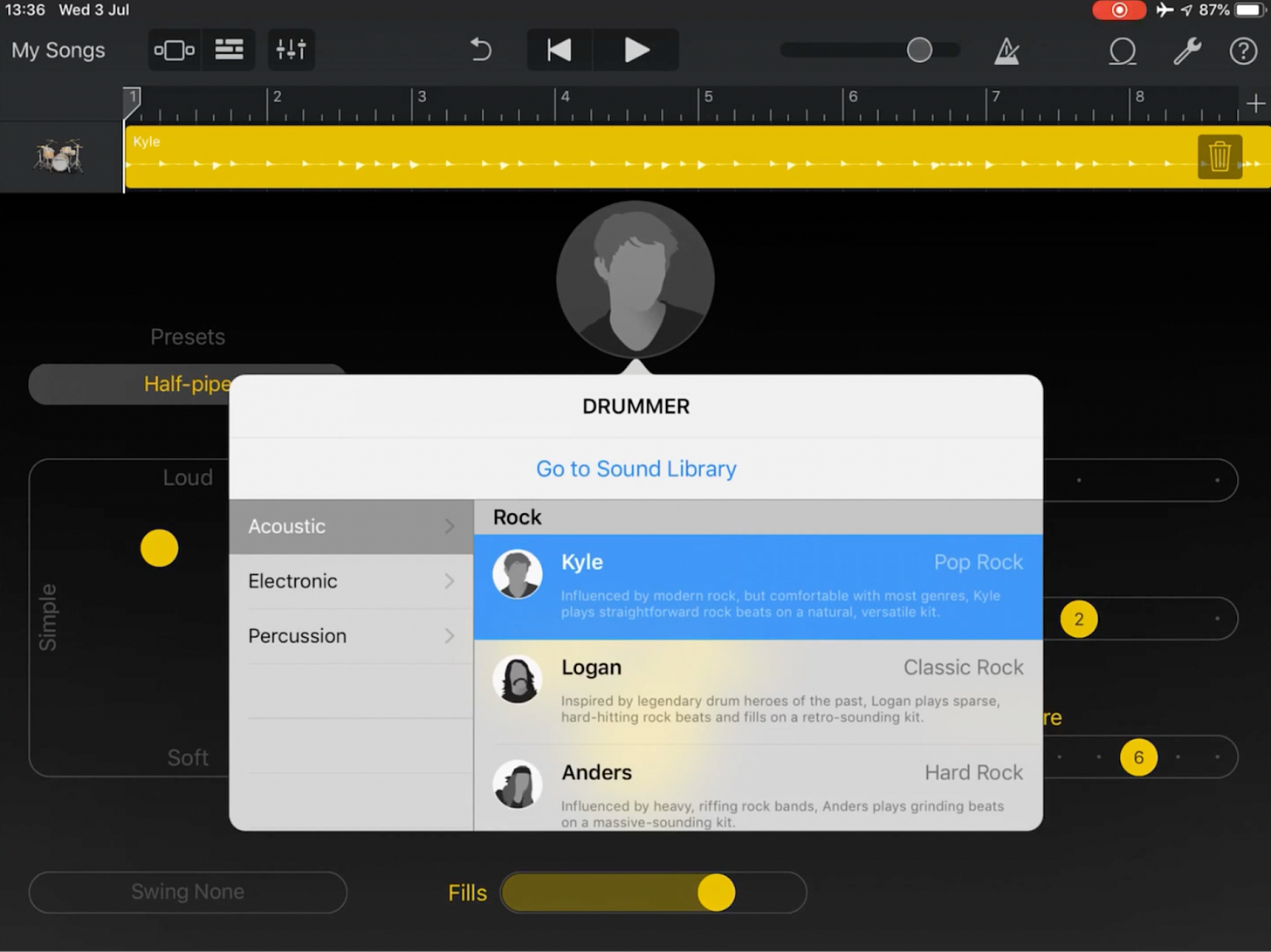

This is the Drummer feature from Apple’s Garage Band app. Here, you can choose a drummer to accompany your tracks. The instructions say, “Each genre comes with a number of drummers who have their own drum kit, percussion instruments and distinct playing style.” Kyle, or Logan, or Curtis or Rose can be adjusted for complexity, they can play fills, and you can tweak them so they give you more or less swing.

These algorithms, with their distinct personalities, won’t just give you an infinite variety of beats, drawing on their combined dataset of all drumming, ever. They will also listen to the other parts of your music and respond. They are not just mimicking a drummer’s sounds. They also promise to improve upon the musical choices that a drummer might make.

But musicians shouldn’t take this sort of thing too personally. If we focus too much on preserving some sort of human essence, we might miss the bigger story, which is a sort of economic and cultural land grab.

I think we should be interested in and worried about a massive fall in the cost of producing stuff that sounds like music. Spotify now has substantial amounts of music generated by AI - much of it labelled ‘functional music’ - almost all of which is sorted by AI, and according to one investigation, some of of which is being listened to by bots in order to boost ratings.

Conclusion

My two examples don’t obviously have much in common, but I think they help put the abstract idea of artificial intelligence in its place.

Driving and drumming are both in some way interactive. They are conversational. Which means they can’t be simply automated. Other parts of our social relationships have to change too.

So to come back to the question of the politics of technology. Who benefits and who decides? And can policymakers anticipate these things and intervene before a technology becomes a fact of life that is hard to shift?

Sociologists of technology have for the last 50 years have been studying how technological artefacts have built-in politics. But technologies are still often seen as neutral tools, that can be used for good or bad purposes. Which means that the politics underlying them is often disguised as mere progress.

When it comes to new technologies, it’s hard to anticipate who the winners and losers are going to be in advance.

It’s tempting to try and predict what the real game is behind self-driving vehicles, to imagine that the conspiracy might be one of surveillance or selling advertising to captive passengers. But actually the mode of innovation is much more speculative. The aim is often to scale for scale’s sake.

I think the history of drum machines shows us something interesting about the politics of technology. The question of who wins and who loses from drum machines is a tricky one. The technology seems to have shifted power from drummers to producers, but it has also handed the means of music production to kids with laptops. n.

And drummers never had much power anyway. Clyde Stubblefield did not just play the Funky Drummer loop. He also composed it. But he saw a negligible share of the success that the sample went on to have. He was just paid a session fee. We should remember that musicians were at the sharp end of the gig economy long before it was called that.

For self-driving cars, we can see some problems with the current direction of travel. If the technology is seen as just a substitute for a regular single-occupancy vehicle, there might be some safety benefits, but problems of car use, car dependency and the traffic and eventually urban sprawl that comes with it could get worse. As it is, the technology risks following the money, providing people who already have plenty of transport with more transport.

With self-driving cars, the start-ups may be stuck in their own story of artificial intelligence. In trying to do something amazing and disruptive, they may end up not being disruptive enough, because they’re failing to acknowledge all the other things required to make the technology work.

If more people are going to benefit from self-driving cars, they will need to work in places that currently don’t have very good transport options, where the current infrastructure might not suit the technology at all. They will also probably need to be shared, in which case a self-driving bus makes much more sense than a self-driving car. And before long, you have a model of public transport that might be rather boring in AI terms, but as a social innovation looks far more innovative.

So I think the optimistic story is that the politics of technologies is actually more open-ended, with the potential for new directions.

I think we can say some things about an emerging ideology of AI. There is a tendency towards what Shoshana Zuboff calls ‘surveillance capitalism’. And we can see a disregard for ownership and copyright in the acquisition of data to feed the machines. We can also see a presumption that bigger is better, which is used to justify a concentration of both computing and economic power. But, like any ideology, this should be discussed and challenged. We should not regard it as inevitable.

So I’m going to end with four quick messages that I hope will allow for a bit more democracy in the politics of artificial intelligence.

First, don’t believe the hype. We shouldn’t accept the story that AI is taking over. Drum machines do not simply replace drummers. Self-driving cars do not directly substitute for cars, nor would we want them to. If we see this as a battle between humans and robots, we will miss all the ways that tech companies will be looking to quietly reconfigure the world.

Hype is not just exuberance or over-excitement. Hype is deliberate misdirection. And the odd stuff about the world ending is all part of the same story. We need to be looking behind the curtain, to see where actual choices are being made.

Second, don’t ask if it’s intelligent; ask if it’s useful. Standards for AI are still inspired by the Turing Test question - is it intelligent? Which is fun, but it’s socially useless. Instead, we need to ask things like “is it useful?” and “is it safe”? For whom?

Third, we shouldn’t just wait and see what AI does. We should also consider why it’s being developed and how it works - where the data is coming from and whether its effects are transparent and explainable. At the moment, the British Government approach is to let regulators catch AI applications in particular areas. The price of that regulatory freedom is a need for serious vigilance, but there isn’t much sign of that. We could be building up to some nasty surprises.

Fourth, we need to include others. The noise about AI is currently drowning out the concerns and the knowledge of a whole range of other people. The agenda for the Government’s AI summit is currently being set by a rather small clique of people. And one reason they’ve come up with such a narrow focus is that they’re ignoring the people who might actually be at risk from AI. If we broaden the range of people involved, we will also be able to realise new opportunities - the sorts of applications that might be transformative for some people but might not be very interesting to people in Silicon Valley.

And finally, we need to make sure that, if the technology is a form of social experiment, the learning from that experiment isn’t all machine learning. There needs to be more social learning, but this requires openness. We should be demanding more from AI companies. As a first step, we should demand that the people testing self-driving cars share data so that we society can start to balance the risks and benefits and other companies can make their technologies safer too.

And we also need independent, critical science. At the moment, AI research requires enormous resources, so it is almost all done within companies. And for a combination of political and technical reasons, it’s hard to get inside AI’s black boxes. This needs to change. The physicist Harvey Brooks had a nice phrase. He said that science should be the conscience of technology. And if universities don’t do this job, I don’t think anybody else will.

P.S. The video of the full lecture is here: